What are the best horror movies of all time? The greatest horror films have been the most popular method of nightmare creation for the past hundred years. The one thing people all over the world can agree on is that they love entering dark rooms and having the worst imaginable creations jump out onto a screen to rattle their unconscious mind and wake up primordial fears. Being scared can be a private thing, but there’s nothing better than sitting in a crowded theater with dozens of other people as if waiting for a sermon and being terrified together with dozens of believers in the power of film.

Trends and monsters have evolved, but the desire to be horrified remains the same, and these films have endured and changed the conversations we have about things that go bump in the night.

Updated on November 10th, 2021 by Mark Birrell: The best horror movies of any era of filmmaking are the ones that–either by intent or pure accident–helped to shape the time period’s understanding of what the genre could offer to audiences.

These groundbreaking films often achieved this by pushing the boundaries of what could be shown outright or even just implied. Many of them were poorly received on release as a result but endured as indelible nightmares that struck a very particular collective nerve. Even if their most shocking visuals no longer hold water with thrillseekers today, the core insights of their journies into the darkest recesses of the human soul still have the ability to send chills down the spine.

Peeping Tom (1960)

• Available on Tubi and Prime Video

Though it was famously reviled upon release to the degree that it is now thought to have effectively ended the directing career of the legendary Michael Powell, the passing of time has revealed Peeping Tom to be one of the most significant developments in the history of horror films. As much a cornerstone to the genre as Hitchcock’s Psycho from the same year, Powell’s movie is far more direct in its approach to using lurid sexuality to examine voyeurism in an age when cameras were getting smaller and smaller, and more and more of life was being filmed.

Powell’s Norman Bates is a young film worker (Carl Boehm) with directorial aspirations and a proclivity for murdering young women with a spike attached to the tripod of his camera, which he uses to film the murders. The brazenly willful absence of any kind of ambiguity in Powell’s statements on cinema’s male gaze and its invasive, penetrating, effect is what gives the film not only its substance but its all-important sense of humor. Peeping Tom can go toe to toe with the most darkly funny movies of Hitchcock’s career.

Cure (1997)

• Available on The Criterion Channel

A series of motiveless murders–disconnected yet all bearing the same distinct hallmarks–bewilder a Tokyo cop (Kōji Yakusho) struggling to split his energy between his job and his wife’s ailing health. But, soon enough, he’s face to face with the hypnotist behind it all (Masato Hagiwara) and that’s when the real questions start.

Cure emerged into a world of audiences hungry for dark psychological thrillers like Se7en and completely defied their expectations for answers and meaning. The story has a dreamlike pace that the audience is completely at the mercy of and a nightmarishly palpable–yet wholly intangible–atmosphere of dread. Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s uniquely cerebral chiller is a haunting example of a mystery that is felt through more than deciphered.

Sisters (1972)

• Available on HBO Max

Brian De Palma’s first foray into thrillers was a landmark moment in not only the legendary director’s career but in the history of horror movies also. Neither one of them would ever be the same again.

As Martin Scorsese began to bring the vivacity of Italian cinema to the world of crime fiction, De Palma began to make horror films that could compare to what filmmakers like Dario Argento were doing in Europe and, though it was far from his first movie, Sisters feels now like the director’s flamboyant debut as one of American filmmaking’s most distinctive voices. Though littered with references to many of Hitchcock’s thrillers, the Psycho-like story of a senseless murder and its hasty coverup exudes its own personality through De Palma’s unwaveringly voyeuristic lens.

Les Diaboliques (1955)

• Available on HBO Max

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1950s suspense films The Wages of Fear and Les Diaboliques have each inspired countless filmmakers since they were released, with the latter having a lasting impact on the very structure of mystery thrillers. It’s one of the earliest examples of a movie that is completely recontextualized by the final twist, transforming the source of the horror into something else entirely the second time that it’s viewed.

Until the finale, Les Diaboliques has an equal chance of being a crime thriller or a ghost story as a boarding school headmistress (Véra Clouzot) and her despotic husband’s lover (Simone Signoret) plot and execute his murder only for the body to vanish and a series of inexplicable events to rattle them further. The horror here exists mostly in the characters’ imaginations and, therefore, the audience’s also, where it lingers long after the final twist of the knife.

The Thing (1982)

• Available on Starz

John Carpenter turned the slasher film into a cottage industry with Halloween, and he turned a combination of classic Hollywood, Chinese, and Italian filmmaking techniques and storytelling into something bold and new by running it through his tense, economical framing, and cutting. The Thing, his remake of Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby’s The Thing From Another World, is a nasty little number, pitting a dozen men, led by a never-better Kurt Russell, against a shape-shifting extraterrestrial that’s woken up from its icy tomb after a thousand years or more.

It takes the form of these men one at a time, pitting them against each other before they can get around to neutralizing the external threat. The Thing remains a potent political film, as well as a model of genius practical effects by masters Stan Winston and Rob Bottin. They don’t make like ‘em like this anymore.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

• Available on Tubi

The first art film and one of the finest early feature-length horror films, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a wonder of German expressionist design and technique, as well as still insidiously frightening almost a hundred years later.

Young German Francis (Friedrich Feher) is intrigued by a carnival sideshow run by an odd man named Caligari (Werner Krauss) who claims power over a sleepwalker named Cesare (Conrad Veidt). When people begin turning up dead, following a demonstration of Caligari’s odd psychological hold over Cesare, Francis suspects the mind-controller might be behind it, and Caligari discovers that Francis has a weak spot in his lover Jane (Lil Dagover). Writers Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer were both veterans of the First World War and intended Caligari as their statement on the corrupting influence of nationalism. Their story was transformed into an incredible work of art by director Robert Weine, whose images are unforgettably haunting.

The Haunting (1963)

• Available on DirecTV and TCM

Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel, The Haunting of Hill House, has been adapted a number of times with each of its retellings taking distinct approaches to the story. As is the case with many successful horror titles, however, the original is still argued by many to be the immovable best.

Two women who have had experiences with the paranormal (Julie Harris and Claire Bloom) arrive at an old country house with an unfortunate history at the behest of a doctor (Richard Johnson) seeking to study the claims of haunting, bringing with him only the young heir to the house (Russ Tamblyn). Together, the four suffer through uneasy conversation, even more awkward flirtations, and the terrorizing presence of a completely unseen force. However, it’s the disorientating odd angles and deceptively tight spaces of production designer Elliot Scott’s sets that give Hill House its chillingly uncanny personality. It’s the perfect backdrop for a classically gothic tale of psychoanalytical terror.

Near Dark (1987)

• Available on Tribeca Shortlist, DirecTV, and MovieSphere

Alluring, dusty, and bloody, Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark is the bar that all-new vampire movies have to clear. A dust devil of erotically charged spree killing, Near Dark follows a pack of nomadic bloodsuckers burning across the American southwest in an RV, leaving nothing but corpses in their wake… that is, until the youngest vampire Mae (Jenny Wright) brings home farmboy Caleb (Adrain Pasdar) with a fresh bitemark on his neck. He has to learn how to ride with them or they’ll leave him to fend for himself with his new dependency on human blood.

Bigelow’s vampire Western rampages across desolate country, finding joy in spending time with the most grisly murderers of the 80s, a decade full of them. Near Dark is as seductive as it is scary.

Nosferatu (1922)

• Available on Tubi and Pluto TV

Director F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, which is among the first vampire movies, is a testament to the unknowable force of nature, of all things wild and ancient. Still the best telling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula story, Nosferatu is about a man named Thomas (Gustav von Wangenheim) sent to sell an English estate to a Transylvanian count (Max Schreck), who instead infects the man with a plague-like disease just before heading to claim his property, leaving a trail of bodies along the way. The only hope of containing the spread of the count’s vampirism are the wiles of Thomas’ fiancé (Greta Schroeder).

Murnau and Schreck came up with a legendary design for their vampire, more rat than man, and he colors the fearsome landscape just by walking on it. The world is a menacing, dark place in Nosferatu.

The House of the Devil (2009)

• Available on Tubi, Vudu, Prime Video, and Peacock

Ti West’s retro-tinged chillers are a consistent delight for modern audiences. He knows how to make films feel old-fashioned without forgetting to forge an exciting new path for himself. Though he’ll have a tough time ever besting the work he did on The House of the Devil.

It surrounds itself with the trappings of a cheap ’80s teen horror film, and then slowly reveals itself to be one of the scariest, savviest horror films of the last three decades. Samantha (Jocelin Donahue) needs money in a hurry and it’s only out of desperation she agrees to babysit for a strange couple who live on the edge of town (Tom Noonan, Mary Woronov). All she has to do is stay out of the child’s room and she’ll make enough money to pay the deposit on her new apartment. Of course, nothing is what it seems and the bodies start piling up. The House of the Devil is a truly terrifying experience, made all the richer thanks to West’s love of the genre.

Vampyr (1932)

• Available on HBO Max

Nearly a decade after the creation of the vampire film, Danish artist Carl Theodor Dreyer, a silent cinema pioneer, unleashed an exercise in dream stoking, a fever for your eyes called Vampyr.

A curious traveler named Allan Grey (Julian West), so taken by the occult that it seems to change his perception of reality, enters a small town unaware that a strange thing is about to befall the land. A man (Maurice Shutz) enters his room, offers the cryptic warning “She must not die” and then vanishes. Grey investigates and finds a family preyed upon by an ancient female vampire (Henriette Gerard). Vampyr is an odd vision of a world suddenly bereft of meaning and will stay with any viewer long after it’s over.

The Devil’s Backbone (2001)

• Available for purchase on Vudu

Guillermo del Toro loves delving into the recent past and playing with storytelling’s tropes and traditions, taking something old and using it to say something new. His ghost story The Devil’s Backbone lifts a stone covering a corner of Spanish history – the brutal treatment of those who fought against General Franco during the Spanish Civil War.

Boys at a boarding school for orphans of the war are terrorized by the ghost of one of their dormmates, who seems to know something about the school they don’t. As his hauntings grow more frequent, things deteriorate at the school, bloody chaos reigning like it did throughout the whole of Spain under the rule of the fascists.

Cat People (1942)

• Available for purchase on Prime Video

Hungarian producer Val Lewton produced nine of the greatest horror films in American history in his short, ill-fated career in Hollywood, and then he died without ever knowing how important his legacy would become. He was one of the first filmmakers to posit that that which is in shadow would be more terrifying than anything the camera could show you. In films like I Walked With A Zombie, Ghost Ship, The Leopard Man and especially his impressive debut as a producer, Cat People, he filled the dark with portent and malevolent ideas more powerful than a monster or specter.

In Cat People, an architect named Oliver (Kent Smith) meets coquettish emigre Irena (Simone Simon) and it looks like love at first sight, but she has a deadly hang-up. When she becomes aroused, she worries she’ll become a panther. Devilishly scary and charming, Cat People works even better than the Universal monster films with which it was designed to compete.

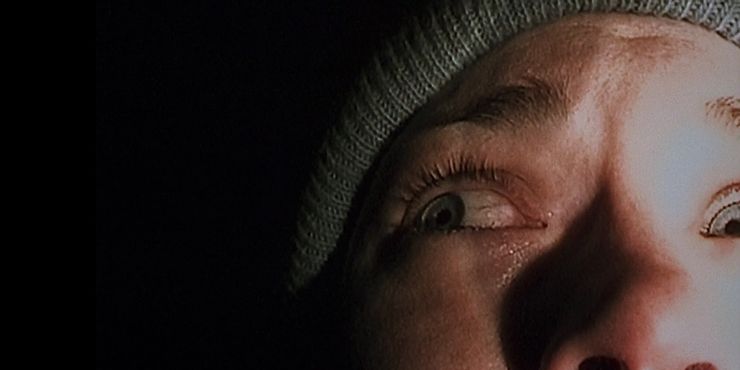

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

• Available on Prime Video

The world changed forever after The Blair Witch Project, even if it took a long time before it became apparent how it had changed. The found-footage subgenre – now a thriving multimillion-dollar addition to both mainstream and direct-to-video horror – would never have become a viable option for filmmakers without The Blair Witch Project turning an immense profit on a relatively minuscule investment.

It also showed how much fear filmmakers could inspire just by promising that there was something in the woods waiting. It wrung every ounce of potential from its incredibly simple premise of three filmmakers heading into the woods to shoot footage for a documentary on the legend of the Blair Witch. It proved that independent filmmakers – with a little ingenuity – could inspire box office figures to rival Hollywood juggernauts and that audiences didn’t mind using their own imaginations a bit during a movie.

The Hills Have Eyes (1977)

• Available on Tubi

Wes Craven may be remembered today as the director who brought post-modernism and gallows humor to American horror, thanks to Scream and A Nightmare on Elm Street, but, before all that, he made movies that seemed genuinely dangerous.

His 1977 film, The Hills Have Eyes, is a great example, a mix of hillbilly black comedy and take-no-prisoners violence and degradation. The Carter Family vacation is interrupted by a clan of cannibals living in a radioactive desert. The suburbanites must learn to fight dirty if they want to survive one day being hunted by their cut-throat adversaries. Craven goes just as low, crafting a gritty, unforgiving look at the things people will do to survive and protect what’s theirs.

Night of the Hunter (1955)

• Available on Pluto TV and Tubi

Robert Mitchum frequently played unshakable tough guys, but he was never more frightening and enthralling than as the desperate killer preacher Harry Powell. While in jail, Powell’s cellmate died without telling him where he buried his stolen loot, so he does what any villain would do – marries the widow (Shelley Winters) so he can get his hands on all that money. But he doesn’t foresee reckoning with her meddling children (Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce).

Night of the Hunter is full of fairy tale symbolism and director Charles Laughton (this was his lone directorial credit) creates a beautifully artificial southern pastoral landscape haunted by Mitchum’s boogieman. The film delivers, in breath-taking style, an eerie testament to the terrifying nature of religion.

Shivers (1975)

• Available on Tubi

David Cronenberg emerged as Canada’s most important sci-fi horror auteur thanks to a relentless schedule and a surfeit of brilliant ideas. He hopped from one human foible and prescient prediction to another, leaving a whole host of unimpeachably brilliant art in his wake. His first proper feature film (after the experimental featurettes Stereo and Crimes of the Future) is about a miasma of sexual paranoia that infects the new tenants at a state-of-the-art apartment complex. A worm passes between victims, turning them into carnally crazed zombies.

Shivers is about many things – the inhumanity inherent in progress, how easily people can lose their identities giving themselves to higher powers – but regardless of whatever subtextual definition jumps out, the eerie power in its images of people destroying each other in sexual congress is everlasting.

Eyes Without A Face (1960)

• Available on HBO Max

New wave outlier Georges Franju (a man in love with early cinema) broke new ground with his masterful Eyes Without A Face, a baroque chiller that paved the way for gore films, Italian giallos, and black-gloved killer movies all over the world.

A little while before the action begins, French surgeon Dr. Genessier (Pierre Brasseur) horribly injured his daughter (Edith Scob) in an accident. He’s now made it his mission to repair her scarred face by any means necessary, even if it means kidnapping young women and stealing their faces until he finds a match. Franju’s film, a carousel of masks, surgery, and deceit, is a timeless, strange work of art, a film that cuts deeply into the viewer’s memory.

Inferno (1980)

• Available on Tubi, Vudu, and Starz

Dario Argento paid delirious homage to the whole of the Italian horror past with Inferno, a witches brew of phantom killers, beautiful color, flamboyant torments, myths, and legends. Inferno, a semi-sequel to his 1977 gory wonder Suspiria, follows a few different figures embroiled in the mystery of a group of witches and warlocks operating out of an old New York building.

Argento inherited the mantle of the master of giallos (whodunnits like Blood & Black Lace with black-gloved murderers dicing up a bevy of victims) from Mario Bava, who assisted in the making of Inferno just before his passing. He imbues every image with preposterously gorgeous and intricate design sense, crafting a film that feels like it could have slipped out of the viewer’s mind, a mysterious vision of the surreal and ominous.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

• Available on HBO Max, Starz, Fubo TV, Tubi, Vudu, Pluto TV, Prime Video, Peacock, and Paramount+

In 1968, George Romero looked around at a world in turmoil (Vietnam, racial tension, high profile assassinations) and let the ugliness seep into his first film, Night of the Living Dead, a righteously angry, aggressive deconstruction of suburban passive aggression. Giving an ancient monster, the zombie, new life that has yet to be drained from it, he found the creature that best reflected a nation in crisis.

Trauma survivor Barbara (Judith O’Dea) meets Ben (Duane Jones), a charismatic Black man, in a remote farmhouse after they’re both attacked by zombies. They barricade themselves inside without realizing there’s a family already inside, led by hot-headed Harry (Karl Hardman). The issue of Ben’s race is never stated outright (Romero knew the images would speak for themselves) but Harry’s mistrust of the otherwise sturdy, handsome, and tough man can’t be chalked up to much else. The zombies never stop pounding on the doors and windows, but the real monsters are already in the house.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

• Available on Tubi, Prime Video, and Showtime

Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still undervalued as a work of precise craft and bountiful art. Everyone knows about the movie and its reputation as one of the most unsettling experiences in all of film history, but many often fail to notice the incredible work it took to have audiences blindsided by the sweltering ghouls at the heart of the story.

Five kids make an unfortunate pit stop at an abandoned house while on a road trip. When they walk to the nearest house to ask for gas, they meet Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen), a hulking mass of muscle with the mind of a child who doesn’t take kindly to strangers. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a most disturbing film, but only because Hooper took such care in building a realistic world for his idealistic heroes to wander into. If the audience didn’t believe these kids still expected kindness from strangers, it wouldn’t hurt twice as bad when the illusion is shattered in an instant.

Kuroneko (1968)

• Available on The Criterion Channel

The legacy of Japanese horror is long, storied, and filled with more uncanny images of ghostly apparitions and things twisted beyond recognition. Director Kaneto Shindo was not a horror director first and foremost, rather an incredibly patient purveyor of quiet communal studies – his interest lay in the way time passes, changing the fundamental nature of survival along the way.

Kuroneko finds a veteran (Kichiemon Nakamura) returning from war a hero, only to learn his wife and mother (Kei Satô and Nobuko Otowa) have been murdered by marauding deserters. Their ghosts now haunt the grove near his home. Shindô conducts the near-silent grove and his bursts of otherworldly violence like an orchestra, in perfect command of the dynamics of his scare scenes and the longing and loss that drives the ghosts and their vanquisher.

The Exorcist (1973)

• Available for purchase on Vudu

William Friedkin put to use his experience directing crime dramas, experimental theatrical adaptations, and documentaries when adapting William Peter Blatty’s best-selling tale of a young woman possessed. Friedkin shreds the audience’s nerves with one unexpected technique or image after another. His trick is making the real-world treatment of an impossible disorder seem just as invasive and terrible as anything the devil could get up to.

Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair) has begun behaving in ways that perplex doctors, psychiatrists, and hypnotherapists alike. She swears, harms herself, and has the strength of two men, and when pressed, she claims to be the devil himself. Two priests (Jason Miller and Max Von Sydow) are brought into to try their luck when treatment and tests fail. Friedkin spares no torment to his characters or his audience in imagining the worst sort of horror.

The Shining (1980)

• Available on HBO Max, Fubo TV, and AMC+

Stanley Kubrick’s productivity slowed to a crawl in the years following The Shining, and while in one sense it’s tragic that audiences never got more films from him, it would have been tough for him to do better than his ultimate psychosexual daydream Eyes Wide Shut or The Shining, one of the finest pieces of horror cinema ever crafted.

Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is a writer looking for his inspiration and a little peace and quiet to do something with it. He takes a job as the caretaker of the creepy Overlook Hotel and soon a creeping disquiet falls over him. Creativity leaves him, replaced by a violent frenzy inherited by the hotel guests whose spirits linger in every corridor. The Shining is a brilliant, bizarre immersion into an artist’s obsessions.

Psycho (1960)

• Available on Showtime

Alfred Hitchcock was a scientist, a man who experimented with the emotions and reactions of his audience, and images were the medium under his microscope. Psycho was his experiment in making a film with the budget of a TV production that could still break expectations.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals a briefcase full of money and stays the night at the homey-looking Bates Motel, run by nervous, awkward Norman (Anthony Perkins). After a strange dinner, Marion takes a shower and then, in one of the genre’s most iconic scenes, meets Norman’s mother, Mrs. Bates. Psycho changed the way people approached horror films. Suddenly no one was safe, no space, no character, nor the audience’s traditional concepts of good and evil. Anything was fair game, thanks to the way Hitchcock expanded even the confines of the horror movie.