Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has taken the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians, and unleashed the most severe humanitarian and refugee crisis in Europe since World War II. It has also dealt a grievous blow to Ukrainian culture: to its museums and monuments, its grand universities and rural libraries, its historic churches and contemporary mosaics.

Since the invasion in February, The New York Times’s Visual Investigations team has been tracking evidence of cultural destruction across Ukraine. By assessing hundreds of photos and videos from social media and Ukrainian government databases, analyzing satellite imagery and speaking to witnesses, we have identified and independently verified 339 sites nationwide that sustained substantial damage. Nearly half are in the mineral-rich eastern region known as the Donbas, where a war has been ongoing since 2014, and where the Ukrainians have recently recaptured villages and towns that fell under Russian occupation. These documented cases represent only a partial picture of the devastation, with much of what is still unaccounted for believed lost.

Libraries, architectural treasures, statues, churches, houses of culture, museums, cinemas, sports facilities, theaters and archaeological sites have been damaged or destroyed. About 180 sites have sustained structural damage requiring at least partial reconstruction, including churches with collapsed steeples or statues missing pieces. And in at least 77 cases, cultural buildings, collections and objects have been completely destroyed.

In the recaptured city of Izium, Ukrainians have exhumed several hundred corpses, some bearing signs of torture; they have also found stone sculptures from the ninth to 13th centuries that were damaged, with at least one shattered to pieces.

In Rubizhne, where the fighting raged for months, a library was reduced to a few dilapidated walls.

Most notoriously, there is Mariupol’s Drama Theater: a cultural landmark whose destruction stands as a signal atrocity of the war, where a Russian airstrike killed many sheltering inside, including children.

The invasion’s aim has been not merely the capture of territory, but “a gradual destruction of a whole cultural life,” said Alexandra Xanthaki, the United Nations special rapporteur for cultural rights. “One of the justifications of the war is that Ukrainians don’t have a distinct cultural identity,” she said, adding that “no one has the right to identify who we are apart from ourselves.”

How much of the destruction has been deliberate? From the first days of the assault, Ukrainian politicians and intellectuals have suggested that Russian forces have directly targeted the country’s heritage. In May, after a museum dedicated to an 18th-century Ukrainian poet burned down outside Kharkiv, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine stated that Russia “fired a missile” to destroy its manuscripts and artifacts. (“Targeted missile strikes on museums: This isn’t even something that some terrorists would think of,” Mr. Zelensky said in one of his nightly addresses.) In the city of Kherson, which Ukraine retook in November, the city’s principal art and history museums reported wide-scale looting.

“This is our country, this is our history. A nation that forgets its past has no future.”

The Times has found that some of the sites were intentionally targeted by Russian soldiers or pro-Russian separatists. Others appeared to be collateral damage. But in case after case, whether the destruction was deliberate or not, the invading Russians showed, at best, a callous disregard for the cultural heritage of Ukraine.

Long before the invasion, President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia claimed that Ukraine had no culture of its own. He has repeatedly called Ukrainian nationhood a fiction, and Russian state media publishes propaganda calling for Ukraine’s total elimination.

“They have their own idea that Ukraine does not exist as a culture,” said Kateryna Iakovlenko, a Ukrainian art historian born in the Donbas region. “That’s why they want to destroy everything: to show that here there is nothing. This is, very clearly, a colonial way of thinking. This is how empires always work.”

The war in Ukraine is a culture war, and the extent of the destruction is becoming clearer. To understand its scale and shock, this investigation focuses on four sites, dotted across eastern Ukraine.

A monastery that predates Catherine the Great, now scarred by shrapnel.

A theater and culture center that enriched Soviet and independent Ukraine, now lying in wreckage.

A library that bridged Ukraine’s linguistic communities, its books now burned, its stacks twisted rubble.

And a monument to a national hero, dismantled on camera by heavy machinery.

Together, they narrate Ukraine’s tangled and transfixing history over the centuries. Now, with their partial or total destruction, they narrate its most recent chapter.

The first barrage of strikes at the Sviatohirsk Monastery of the Caves, one of the holiest sites in the Orthodox Church, came just a couple of weeks into the war.

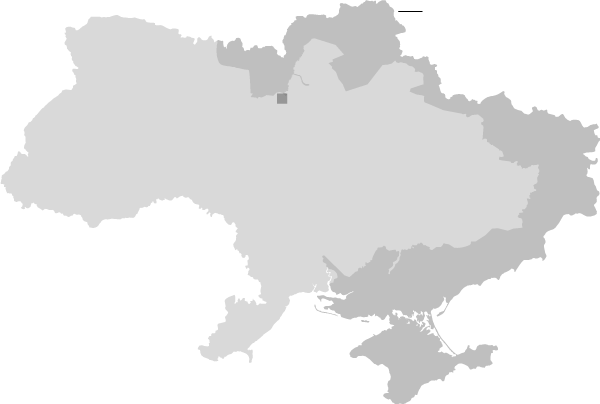

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

religious sites

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

religious sites

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

religious sites

At around 10 p.m. on March 12, a projectile splintered the complex’s wooden steeples. It shattered the glass. It reduced marble statuary to chunks. Some of the several hundred Ukrainians who had sought safety behind the monastery’s walls, including children, fled into the night air. The monastery’s onion-domed churches and hillside sepulchers, part of a complex dating back more than four centuries, were in the line of fire.

A church and a refectory were battered during more strikes in early May. The gravest damage came on June 4 and 5, as Russian soldiers were fighting to take the town of Sviatohirsk, just across the river. A direct hit on one of the men’s dormitories on the monastery grounds killed three people sheltering there. A large wooden church went up in flames in the hills above the monastery; when the fire died down, all that was left were the foundation and some iron nails. Russian forces took control of Sviatohirsk after that, but the monks who lived there, and the nuns and displaced people who had joined them, did not leave the sprawling complex, which in Eastern Christianity is known as a lavra.

![]()

Hundreds of civilians sought refuge at the lavra starting in the early days of the war. This was the scene in one of the monastery’s cavernous bunkers in June, just days before Russian forces took control of Sviatohirsk.

Andrew E. Kramer, a reporter for The Times, reported from inside the lavra as it came under attack in June: “During a recent visit to the monastery, shells striking the grounds threw up columns of dirt and smoke, followed a few seconds later by the pattering noise of debris falling down on the church domes. Monks ran for cover, their black robes flapping.”

The destruction that the Russian invasion rained down on the Monastery of the Caves was not an outlier. The Times has identified 109 churches, monasteries and other religious sites across Ukraine that have been damaged or destroyed since the war began. Many, like the lavra, are places of Orthodox worship, though several mosques and a synagogue were also damaged. Wooden churches have been particularly endangered: 19th-century wood structures burned to their foundations near Kyiv and Zhytomyr. Even near Lviv, in the relatively safe west of the country, a Baroque 18th-century Catholic church recently saw its windows blown to pieces after rockets landed nearby.

Wars and soldiers decimated many sites of worship and pilgrimage over the past century, from Coventry Cathedral in England to the Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan and the Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo, Syria. Still, the bombardment of the Sviatohirsk monastery has special resonance in Ukraine, underscoring the knotty history of Russian and Ukrainian religious orthodoxy and the cultural pretexts for the invasion.

![]()

A pre-Soviet postcard from the Sviatohirsk Monastery of the Caves that reads “Greetings from the holy mountains.”

Standing on the high right bank of the Siverskyi Donets River — the river that gives the Donbas its name — the monastery has faced powerful enemies over the centuries. Catherine the Great expropriated its surrounding lands in the 18th century. Bolsheviks shot its monks in the first years of the Soviet Union, and converted the complex into a sanitarium and a cinema.

Still, the monastery endured. The “Holy Mountains” in Sviatohirsk remained a spiritual and mystical site regardless of sect allegiance, and since the independence of Ukraine in 1991 it has been a photogenic tourist draw for the faithful and secular alike.

Diana Serbina, who grew up in the region but is now displaced in Lviv, used to visit frequently with her family, buying gingerbread from the monks and lighting candles in front of the altars.

“Until the last moment,” she said, “I’d thought that no one would touch Sviatohirsk.”

![]()

![]()

Diana Serbina’s first visit to the monastery, in the summer of 2008 (left), and a 2018 trip with her family (right). She traveled to Sviatohirsk several times a year.

Ukraine is a religious country. Before the war, more than a third of its citizens said they attended worship services regularly, according to a Pew Research Center survey. Most believers in Ukraine and Russia belong to branches of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and both Russians and Ukrainians trace the history of Christianity in their countries to the conversion of Vladimir the Great (later Saint Volodymyr) in Kyiv a thousand years ago.

But in the past 10 years, political and religious struggles led the Orthodox Church to split into three competing branches in Ukraine: one allied with the church in Moscow, and two others with presiding bishops in Kyiv.

“Theologically, they have no differences,” said Archpriest Oleksandr Shmurygin, a priest of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate. “The difference is only administrative — and, perhaps to some extent, mental.”

Worshipers praying and lighting candles at the Sviatohirsk Lavra, February 2019.

Ukrainian political leaders already looked upon the Moscow-aligned church with suspicion before the war, and Mr. Zelensky has now proposed banning it within Ukraine. The Sviatohirsk lavra was one of these Moscow-aligned houses of worship, and when the war began its monks were still under the spiritual authority of Patriarch Kirill in Moscow, who has blessed the Russian invasion. None of that was enough to protect the lavra when the Russian soldiers arrived.

![]()

Orthodox Christmas, January 2022.

Now, as Christmas approaches, some residents who fled during the fighting are returning. Locals aligned with the occupiers and those who supported Ukraine are eyeing each other warily. The lavra’s doors are off their hinges and transoms have buckled; the brick walls of the churchyard bear the cavities of artillery. The wrought-iron bridge once festooned with newlyweds’ “love locks” has been blown up, severing the lavra from the town of Sviatohirsk.

“I very often dream at night that I’m walking around the city, everything’s destroyed, and I look around and I want to cry.”

![]()

The bridge connecting the monastery to the town of Sviatohirsk, November 2022.

The Russian occupation last summer was notable for its silence, at least when the guns died down. “All the time that Sviatohirsk was occupied, while there were active hostilities, there were no bells,” said Valeriia Kostiushko, a Sviatohirsk local now displaced in Dnipro. “We’re all so accustomed to living with this beautiful sound in the background.”

When the Ukrainian army retook Sviatohirsk in mid-September, the bells of the lavra rang out for the first time in months. “The neighbors started hugging and crying,” said Ms. Kostiushko, recounting a report she got from the town. “This is such a bringer of peace. These bells gave them hope.”

The Railway Workers’ House of Science and Technology in Lyman — a people’s palace for the arts dating to the Soviet era that provided a grand stage for visiting artists, folk ensembles and community performances at Christmastime — came under attack the night of April 30.

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

community cultural

centers

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

community cultural centers

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

community cultural centers

A cleaner helped evacuate 30 people, some elderly, who were sheltering in the basement, said Inna Trush, its director. By 4 a.m., the building was completely ablaze. The Russians captured the city, a strategically vital railway junction, in late May.

When Ukraine retook Lyman at the start of October, the returning townspeople found their cultural center reduced to a hollow shell. In the grand lobby, with its geometric marble columns and decorative paneling of lyres and train engines (a tribute to the town’s rail workers), windows were shattered and doors blown off. The once elegant theater, with its blond wood paneling and seats upholstered in red, was reduced to an open-air scrapyard, cluttered with charred bricks and mangled beams. The stage: just a shelf strewn with rubble. The ceiling was only sky.

![]()

![]()

Satellite images of the Railway Workers’ House of Science and Technology, captured on March 25, 2022 (left), and on Aug. 24, 2022 (right).

Maxar Technologies

“I still remember the first time I performed on the stage of the palace,” said Ms. Trush, who fled the country this spring. “I was 7 years old. I played the grand piano.”

It pained her to recite the details of its destruction.

“My hands tremble, because it all hurts so much,” she said.

The Times has identified at least 37 community cultural centers that have been damaged or destroyed in Ukraine since Feb. 24. The active house of culture in Irpin, a Kyiv suburb, had its roof blown open and its auditorium eviscerated. To its northwest, the windows cracked apart and the ceilings fell in at Borodianka’s house of culture. Fire ravaged another almost 100-year-old house of culture in Bakhmut, in eastern Donetsk, engulfing its roof and walls.

The houses of culture were testaments to the complex intertwining of Russian and Ukrainian cultural history: the legacy of Russian imperial rule, the two countries’ shared Soviet legacy, and their division and antagonism over the last 30 years. After the October Revolution in 1917, Ukraine cycled through a succession of short-lived polities before its absorption into the Soviet Union. At the time Lyman’s cultural palace was built in 1929, Moscow still promoted Ukrainian language and culture, through a policy known as korenizatsiya (“indigenization”).

![]()

Run either by local chapters of the Communist Party or trade groups, houses of culture were a staple of Soviet cities and towns. Lyman’s house of culture was built in 1929.

![]()

The main theater could seat 850 people. “The stage was equipped with modern spotlights and had good acoustics,” said Inna Trush, the director. “We no longer have all this.”

During the Soviet period, every major city and many smaller towns had an arts hub like Lyman’s: a palace of culture where workers, retirees and children could read, sing, dance, take courses, hear lectures and imbibe the official state ideology. By the 1980s, there were more than 100,000 operating across the Soviet Union.

“I have a dream that the palace will celebrate its centenary. There is time. Seven years are enough for reconstruction.”

Citizens kept them operating after independence, and reoriented them for a democratic Ukraine. The country has lavish art museums in Lviv, a stately opera house in Odesa, world-renowned nightclubs in Kyiv — but further afield, in towns like Lyman, the houses of culture have remained essential institutions for arts and heritage. Lyman’s offered English classes, billiards, singing groups and a puppet theater for children. There was an ensemble for locals who wanted to perform Ukrainian folk songs, and another for teenagers who preferred pop. The town had been losing population, like many places in the Donbas region, yet Lyman still invested in its house of culture, putting in new curtains and artwork in 2020.

“If anyone had a hint of a voice, they’d start singing,” remembers Olena Parhomenko, an employee of the house of culture. “What else is there to do in a small town? Everyone, everyone went. And the ones that didn’t, they came as audience members.”

Inna Trush, Olena Parhomenko and others displayed their artistic talents at the 90th anniversary gala for Lyman’s house of culture in 2019.

![]()

“I can’t reconcile the fact that the palace is destroyed,” said Ms. Parhomenko, pictured in the building’s lobby in 2021. “The walls, with their history, they’re still standing. So I know I’ve got something to hold on to.”

Ms. Parhomenko was the fourth generation in her family to orient her life around the house of culture, where her great-grandfather had once conducted a choir. She began dancing and singing on its stage as a child, and her talents led her all the way to Ukraine’s version of “The X Factor.” (She came in fourth place, performing “La Isla Bonita.”)

When Times journalists toured Lyman after the Russian retreat in October, the city had no running water or electricity. Locals had been cooking on campfires for months already. Winter approached. Ms. Parhomenko, who crossed the whole of Ukraine during the war to shelter near Ivano-Frankivsk, said that she missed the theater even more than she missed her home.

“I just want to go back to the palace,” she said. “There are columns in the foyer there, and I just want to hug them. I dream about hugging them.”

The Sievierodonetsk City Public Library stood right in the center of the city, and Yuliia Bilovytska, the head librarian, feared for its survival from the first days of the Russian assault.

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

libraries

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

libraries

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

libraries

On March 2, she said, she had to take shelter with her family and her dog as projectiles rained down. When she emerged, she found that the library’s windows had been broken to pieces, and its computers had been looted. She and her colleagues thought about moving the remaining equipment to the basement, but the underground space had taken on a more urgent function: to shelter residents from the bombardment. (The library was powered separately from the main grid, Ms. Bilovytska explained, offering neighbors a warm refuge amid widespread electricity and gas outages.)

![]()

Satellite imagery from May 30, 2022, showed smoke rising from the library.

Maxar Technologies

By late May, Sievierodonetsk saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war. At one point the front line ran directly along Central Avenue, in front of the library. On May 30, as the battle intensified outside, flames coursed through its stacks. Smoke could be seen rising from the building through a gaping black hole in the roof.

The library held an archive of periodicals and small-run publications from Sievierodonetsk’s early decades, which the librarians assume to be irreplaceable. Local authors’ publications, many with inscriptions, were also lost, said Ms. Bilovytska. There were withered flowers mixed in with the rubble, the remnants of a horticultural show that took place just days before the onslaught.

![]()

In late February, a local botanist installed an exhibit of violets and cape primroses at the Sievierdonetsk library. By early March, the flowers had died among the rubble in the freezing cold.

“The cultural losses are simply insane,” said Ms. Bilovytska, who is now living near Kyiv. “As long as we are alive, there is memory. But books preserve it longer.”

The Times has identified at least 24 libraries that have been damaged or destroyed since February. Along the road to Kyiv, the fighting left libraries in Irpin and outside Ivankiv in tatters. In the northern city of Chernihiv, Russian bombs laid waste to a children’s library in a building dating back to the 19th century. In the tiny village of Pidhaine, with an aging population of just 200 or so, a little library was smashed to matchwood. (Many of Ukraine’s devastated houses of culture and schools also had library collections, and several literary museums have been demolished.)

“It’s not just that libraries are being destroyed physically as buildings — ideologies are being destroyed as well,” said Svitlana Moiseeva, who has been a librarian in Ukraine for more than three decades.

Sievierodonetsk’s ravaged library, the largest of the city’s five public libraries, has particular significance for the war — it was an exemplar of Ukrainian bilingualism, and the shifting statuses of the Russian and Ukrainian languages. While the nation’s official language is Ukrainian, researchers estimate that a third of the population speaks Russian at home. Sievierodonetsk was a bilingual city, and so was its library. It had a collection of some 170,000 volumes in both languages: Adults could borrow rare Russian titles dating from the Soviet era, while children could peruse “Harry Potter” books in Ukrainian.

![]()

The outbreak of war in 2014 led many families from eastern Ukraine to seek refuge in Sievierdonetsk. The library put together events to help integrate new residents. “They were no longer strangers in a strange city,” said Yuliia Bilovytska, the head librarian.

In 19th-century czarist Russia, the Ukrainian language was suppressed; under Stalin in the 1930s, Soviet writers working in Ukrainian were persecuted and sometimes executed. Today, Mr. Putin minimizes Ukrainian as a folksy dialect of Russian, and argues that works of poetry and fiction in that language constitute part of the literature of “the greater Russian nation.” Librarians and government officials have said that the Russians have purged Ukrainian-language volumes and histories of Ukraine from some libraries in occupied regions. (Ukraine has engaged in literary suppression of its own, restricting the import of Russian titles in 2016 and taking further steps this year to ban imports from Russia.)

Sievierodonetsk, like many places in the Donbas region, is a young city, founded in the Soviet era alongside a chemical plant, and growing into a major industrial center after World War II. The surrounding region was home to one of the greatest concentrations of Russian speakers in Ukraine. But since 2014 — in the wake of the Maidan revolution, the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas — there had been signs of a growing embrace of the Ukrainian language.

![]()

![]()

The Sievierodonetsk library opened its doors to readers in 1961 with only 1,070 titles on its shelves. By 2022, its collection had grown to around 170,000 books.

“The destruction of libraries is like cutting out a part of our heart.”

You could see this at the Sievierodonetsk library, where last year they celebrated the sesquicentennial of Lesya Ukrainka, Ukraine’s great modernist poet and playwright. In December, children danced around a Christmas tree in the library’s multipurpose room, singing carols in Ukrainian. BIBLIOTEKA, read the sign over the entrance: “library,” rendered the Ukrainian way, with the letter “I” rather than the Russian “И.”

Sievierodonetsk fell to the Russians in June, after weeks of brutal street fighting, which left some 90 percent of its buildings in ruins and forced 95 percent of its population to flee. Now it is a “dead city,” in Mr. Zelensky’s phrase: smashed, scorched; nearly flattened, nearly futureless.

![]()

![]()

The library offered internet access to the public and computer classes for older residents and job seekers (left). “We transformed into fairy tale characters,” Ms. Bilovytska (right) said about the storytelling events they organized for children. Her Ice Queen costume, which she made from her wedding dress, was left behind when she fled Sievierodonetsk in April.

Among those who fled was Diana Trunova, a publisher who went to the Sievierodonetsk library throughout her youth and then with her own children. “We spoke mainly Russian both at home and at work,” she said. “But we live in Ukraine, and our children study in kindergarten and school in Ukrainian.”

She and her family spent almost a month in a bomb shelter before fleeing west to Lviv — the other side of Europe’s second-largest nation.

“The fact that I was born in another part of Ukraine does not make me less Ukrainian than those who live in territories where the Ukrainian language prevails,” Ms. Trunova said. “It does not reduce my desire to drive away all the evil spirits that have now occupied our territories.”

In Manhush, a village outside Mariupol, satellite imagery captured what appeared to be mass graves dug in country fields. But it was a different kind of wartime operation that brought heavy machinery rolling in weeks later: uprooting a statue of a Cossack general.

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

monuments

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

monuments

Areas controlled

by Russia at any

time since invasion.

Damaged or destroyed

monuments

Russian and Soviet flags waved on May 7 as a crane winched the white stone statue of Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, a 17th-century military hero, off its pedestal outside the town’s administrative headquarters.

Its subject was old, but the statue was new. The town of Manhush inaugurated it in 2017, in the wake of the Maidan revolution and in the midst of a running war with Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas region. A month before it was removed, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine had proclaimed Konashevych the patron saint of the Ukrainian army.

“I looked at the monument often,” Dmytro Chernytsia, a former local government official, said during a recent video call from a bomb shelter. Mr. Chernytsia, who now serves in the armed forces, was present at the statue’s inauguration. He was particularly interested in how the 17th-century general held his sword aloft with both palms — a gesture of peace that could quickly become its opposite.

Dmytro Chernytsia and others unveiling the Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny statue in Manhush in 2017.

With a blade like that, said Mr. Chernytsia, “you can slice bread or you can kill for your homeland.”

“If you are a friend or comrade, we will welcome you into our homes,” he continued. “If you are an enemy, you will die by that sword.”

Monuments appear to have been deliberately targeted more than any other type of cultural site, the Times investigation found. Soldiers and amateurs alike have filmed their removal or ruin, and in some cases, like the Manhush statue, the footage has been disseminated online as official Russian propaganda. The Times has identified at least 48 damaged and destroyed monuments and memorials, including gravesites, principally in eastern Ukraine. They commemorated Cossack commanders, Ukrainian cultural pioneers, Soviet war dead and figures of recent independence movements.

Elsewhere in Manhush, a bulldozer overturned a memorial to Ukrainians who fought to repel the Russian-backed occupation of the region that began in 2014. Like the Konashevych statue, that memorial was erected by the local government in concert with the Azov Regiment, a nationalist group whose early ties to far-right figures have been used by the Kremlin to falsely paint Ukraine as fascist, and to seek to justify its assault as “denazification.” An official working for the new pro-Russian administration in Manhush said in a Russian state media interview that the monuments there had been removed because of their connection to Azov.

But many other monuments with no ties to nationalist groups have been intentionally toppled or damaged since the invasion began. In the ruins of Mariupol, the occupying forces dismantled a memorial to the Holodomor, the famine engineered by Stalin that killed millions of Ukrainians in the 1930s. A memorial to Ukrainian victims of the Holocaust, erected in Kharkiv in 2002, was badly damaged during fierce fighting in March. And in Borodianka, a suburb of Kyiv, a bust of Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet, took a bullet in the head.

Pro-Russian separatists stole a memorial to the Ukrainian opera singer and fighter Wassyl Slipak after the area was occupied by Russian forces this summer.

“They aren’t just dismantling the monument; they are trying to dismantle the memory,” said Anna Murlykina, a journalist from Mariupol who runs a local news website. “Ukraine has been trying to restore its history for 30 years. In order to dominate these territories, it is necessary to return to the state of the Soviet era. Everything needs to be erased again.”

Monuments commemorating the Maidan revolution and fallen soldiers from the subsequent war in Donbas have been frequently targeted. In Kherson, the occupying forces used an armored vehicle to rip the Ukrainian coat of arms off a memorial to locals who died in combat. Near Bakhmut, where a monthslong battle has devolved into trench warfare, pro-Russian separatists toppled and later stole a memorial to a Ukrainian opera singer who fought in the Donbas war and was killed in 2016.

Ukrainians have been engaged in dismantling monuments as well. More than a dozen statues of Alexander Pushkin, the Russian poet, have fallen since February. Some Soviet mosaics and monumental statuary have also been slated for removal in recent years as a matter of Ukrainian state policy — triggering the ire of some Ukrainian intellectuals, such as the Kyiv artist collective DE NE DE, who are fighting to preserve the country’s Soviet heritage as part of Ukrainian history.

![]()

In Uzhhorod, Zakarpattia, local authorities removed a bust of Alexander Pushkin in April (left). The same month, a Soviet monument to Ukrainian and Russian friendship was taken down by the government in Kyiv (right).

On Dec. 24, the war will enter its 11th month. Monuments across Ukraine remain wrapped in flame-retardant blankets, or surrounded by piles of sandbags. Church windows are still boarded up. Damaged sites face the additional threats of ice and snow, though international organizations and local citizens have stepped up efforts to protect museum collections, libraries and architecture. And even as attacks have knocked out power and left swaths of the country in the cold and the dark, Ms. Murlykina, the journalist from Mariupol, sees the attacks on cultural heritage as central to the conflict.

“It is not just the war for monuments,” she said. “It is the war for the future, for consciousness, for the right to teach children in a truthful way.”

Sheltering now, nearly 200 miles from her annihilated hometown, Ms. Murlykina watched the video of the dismantling of the statue in Manhush that had commemorated Ukraine’s greatest military leader. When she looked away from her screen she felt a curious mix of despair and conviction.

“On the one hand, it really hurts to watch,” she said. “On the other hand, there is the absolute belief, the inner awareness, that we will restore everything.”