CAIRO — When the University of Washington Ph.D. student was arrested in Cairo while researching the Egyptian judiciary, he asked the prosecutor for the accusations against him. Joining a terrorist group, he was told, and spreading fake news.

“I was pleased for a second, because these are so absurd, there’s absolutely no evidence, it’s very, very easy to refute,” said the student, Waleed K. Salem, 42. But as he found out, “Once you’re slapped with these labels, you go into the black box.”

He was now trapped. Held in pretrial detention, Mr. Salem was never tried or formally charged with a crime. Instead, every time he maxed out the legal detention period, a prosecutor extended his imprisonment in a hearing that usually lasted about 90 seconds.

“The first five months, you’re trying to convince yourself it’s just five months,” Mr. Salem said. “But after five months come and go and you’re still there, now you start to fear the worst.”

President Biden’s meeting with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia on Friday was a conspicuous U-turn for the president, who once pledged to ostracize the prince over human rights atrocities.

But Mr. Biden will meet another Arab leader in Jeddah on Saturday whose human rights record he has also denounced: Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Egypt holds tens of thousands of political prisoners, according to rights groups and researchers, their ranks swelled by Mr. el-Sisi’s crushing campaign against dissent.

Mr. el-Sisi’s predecessors also jailed critics. But he has done so on a vastly greater scale, largely by transforming the routine administrative procedure of pretrial detention into Egypt’s chief engine of mass repression.

Security forces arrest people from the street or from their homes, disappearing them without notifying families or lawyers. When the detainees surface in custody, prosecutors accuse them of terrorist activity and detain them for months or years on end without ever having to prove their case at trial.

The crackdown that ensnared Mr. Salem in 2018 has caught up Egyptians of every stripe, branding them as enemies of the state for even the mildest criticisms. One case involved the arrest of a politician mulling running against Mr. el-Sisi; another, two women on a Cairo subway overheard complaining about rising fares; yet another, a young conscript who posted a Facebook meme of Mr. el-Sisi wearing Mickey Mouse ears.

Some political prisoners have had trials, if only perfunctory ones, and have faced harsh sentences.

But pretrial detainees are not granted even such cursory justice.

In the special terrorism courts where the el-Sisi government funnels political opponents, the authorities do not file formal charges, present evidence or, in many cases, allow detainees to defend themselves before locking them up.

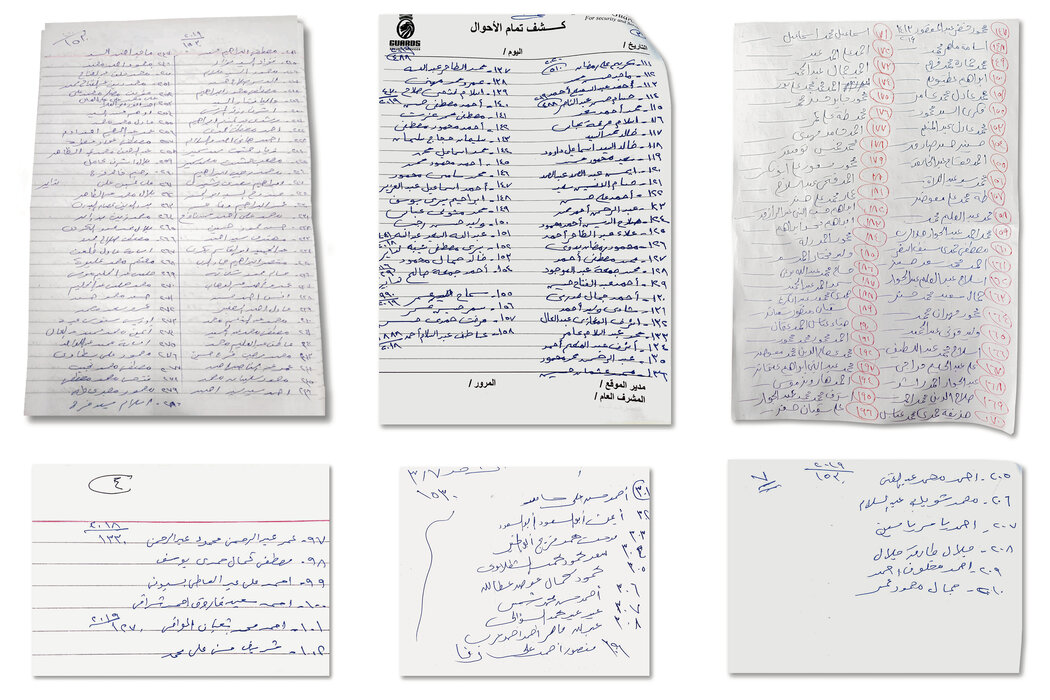

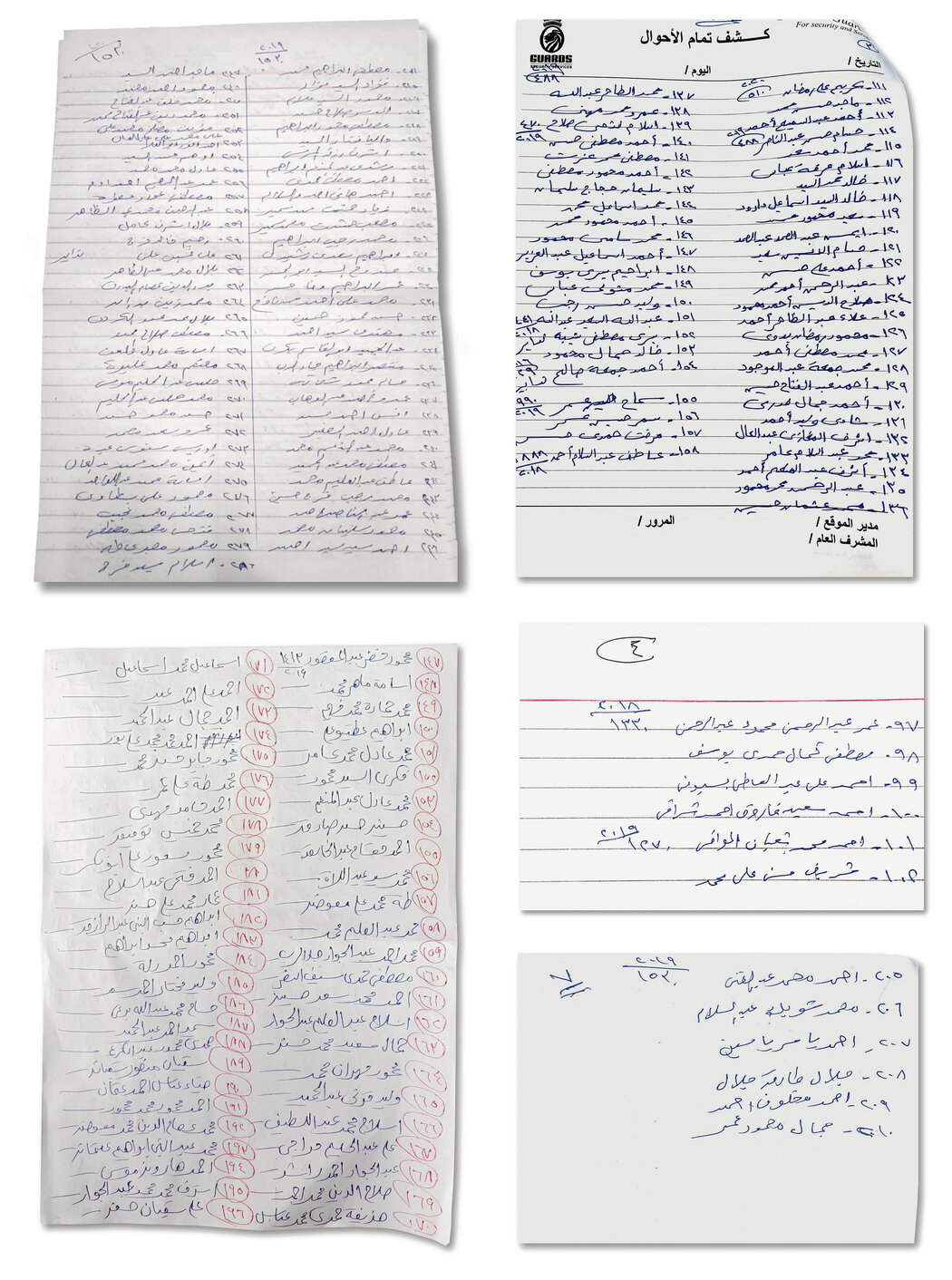

No public records exist of how many people are held in pretrial detention. But an analysis by The New York Times of handwritten court logs, painstakingly kept by volunteer defense lawyers, shows for the first time the number of individuals detained without trial and exposes the circular legal process that can keep them there indefinitely.

To estimate how many people were caught in the loop, The Times matched the handwritten names and case numbers of people who made multiple court appearances. Alternate spellings and duplicate case numbers were often used, making a perfect record impossible. But we wrote custom software to screen them and carefully checked each record to account for similar spellings.

The true total is likely greater than our estimate, which is only a partial snapshot of the system.

The estimate leaves out detainees who were arrested and released before the five-month mark, the first time a court appearance is required. Nor does it include Egyptians prosecuted outside the capital. And there is no public accounting of prisoners held off the books in police stations and military camps or those who have simply vanished.

The Times analyzed handwritten court logs like these, kept by volunteer defense lawyers, to estimate the number of people held in pretrial detention.

The Times analyzed handwritten court logs like these, kept by volunteer defense lawyers, to estimate the number of people held in pretrial detention.

“More and more ordinary people have been swept up,” said Khaled Ali, a rights lawyer. Pretrial detention is supposed to give the authorities time to investigate cases, he said. “But in reality, it’s being used as a punishment.”

Human rights groups estimate that Egypt holds 60,000 political prisoners, a number that includes pretrial detainees as well as those who have been tried and sentenced, terrorism suspects as well as those accused of simply having wayward political opinions.

Egypt has long denied holding any political detainees. People arrested on accusations of criticizing the authorities, officials say, are threatening public order.

“Even protesting — there’s a law against it,” Salah Sallam, a former member of Egypt’s government-appointed National Council for Human Rights, said in an interview. “I can’t call someone who’s conspired against the state a political prisoner.”

In the last few weeks, however, some officials have begun to acknowledge the practice of imprisoning people for their political views, saying it was necessary to restore stability after the turbulence of Egypt’s 2011 Arab Spring revolution.

“There are times when the country is going through rough periods, like a period of terrorist attacks or economic reforms, when measures have to be taken,” Tarek el-Khouly, a member of Parliament, said in a recent interview.

Egyptian police officers patrolled a Cairo neighborhood in 2016 to head off potential anti-government protests.

Mahmoud Khaled/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

In prison and court, there was never any pretense about the nature of the crime. According to former detainees and lawyers, guards and judges openly refer to detainees not linked to violence as “political.”

Officially, however, most pretrial detainees are accused of joining terrorist groups whether or not they have been linked to violence, allowing the authorities to round up perceived opponents in the name of security. The government does not distinguish between a militant planting bombs and a Facebook user grousing about rising prices: Both are labeled as terrorists.

An Egyptian research group that tracks the justice system has found that about 11,700 people were charged with terrorism offenses from 2013 to 2020. The vast majority, rights groups say, have not been linked to violent extremism.

“It just shows you how this terrorism charge has lost any meaning,” said Mohamed Lotfy, the executive director of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, which represents political prisoners. “It’s a preposterous, irrational thing.”

The Detention Cycle

The legal framework of pretrial detention gives it the veneer of due process.

But interviews with dozens of people — including detainees, former detainees, detainees’ families, lawyers, activists and researchers — portray a system in which prosecutors and judges routinely minimize or ignore any rights the detainees have.

During the first five months of detention, detainees can legally be held for two weeks on the basis of accusations leveled by prosecutors, a period that can be extended if prosecutors request more time to investigate. That is precisely what prosecutors do for most detainees, renewing their detentions every 15 days without formal charges filed or evidence presented.

After five months, the detainee gets a hearing before a terrorism court judge, who can renew detentions for 45 days at a time.

In theory, the hearings give detainees another chance to challenge their detentions. In reality, defense lawyers are rare and evidence is almost never shown, former detainees and lawyers said.

The entrance to Tora Prison in Cairo, “the place that no one gets out of,” as one guard put it.

Khaled Desouki/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The hearings are closed to the public, even to detainees’ families. Defendants appear in crowded, soundproof glass cages that are muted to keep them from being heard — or even from hearing their own judgments.

At five months in pretrial detention, Mr. Salem, the graduate student, advanced to terrorism court, where he waited in a soundproof cage with dozens of other defendants. When his name was called, the judge pressed a button, unmuting the cage and allowing him to speak.

“Your honor, I’m just an academic like you,” he began. “I have a daughter, please consider this.”

A lawyer who had been designated to represent Mr. Salem and half a dozen other defendants stepped up to the bench. He argued that prosecutors had shown no evidence, that the charges were vague and baseless.

The judge extended Mr. Salem’s detention for another 45 days.

He was released in December 2018, nearly seven months after his arrest. But he remains banned from travel, preventing him from seeing his 13-year-old daughter, who lives in Poland with her mother.

“I knew what to expect,” Mr. Salem said, “but hope is a tenacious thing.”

The coronavirus has put even more distance between detainees and a fair hearing. Since last year, lawyers say, officials have taken to transporting some detainees to chambers below the courtrooms without bringing them before a judge, a way of satisfying the procedural requirement of transferring them to the courthouse while keeping them from petitioning the judge, and a timesaver into the bargain.

The authorities cast such measures as Covid precautions, citing the cheek-by-jowl courtroom cages. That explanation would be more credible, lawyers and rights groups say, if prisons were not bulging with overcrowded cells, if authorities had not failed to give detainees protective equipment or if they had not kept families from supplying it.

Most hearings last just a few minutes before the judge signs the renewal orders.

“This whole thing has nothing to do with justice,” said Khaled el-Balshy, the editor of Darb, one of the few remaining media outlets that do not toe the government line. “We’re all playing a role. It’s all a charade.”

The 45-day stints can be renewed repeatedly for up to two years. After that, the law requires that the detainee be released, though that does not always happen. In many cases, prosecutors simply bring a new case, starting the two-year timer all over again.

At least 1,764 detainees were recycled into new cases from January 2018 to December 2021, according to the Egyptian Transparency Center for Research, Documentation and Data Management.

For more than a quarter of them, the center found, it was at least the second time they had been shunted into new cases. For some, it had been as many as seven times.

Ola Qaradawi, 56, and her husband, Hosam Khalaf, 59, were arrested while on a family vacation on Egypt’s north coast in 2017.

The couple, both of whom hold United States permanent residency, were accused of having ties to a terrorist group. But the real crime seemed to be that they were related to a prominent critic of the military coup that brought Mr. el-Sisi to power in 2013.

After two years in prison, Ms. Qaradawi in solitary confinement, they were ordered to be released.

But instead of sending them home, guards took them to prosecutors, who accused them of committing new crimes while in prison.

“We were actually planning the party, thinking we were going to celebrate when they came out,” said their daughter, Aya Khalaf, an American citizen. “It’s like everything you’ve gone through has gone down the drain, and now they have the right to hold you again for another two years.”

Ms. Qaradawi was finally released in December 2021 after four years in detention. Her husband remains in jail.

Although there is a legal distinction between pretrial detention and a prison sentence, detention often amounts to harsh punishment.

Prisoners are held in overcrowded, filthy jails, sometimes for years. They are often deprived of visitors, bedding, food and medical treatment. Torture is common.

Rights groups say hundreds of people have died in Egyptian custody over the past five years from a combination of abysmal conditions, abuse and lack of health care.

A Widening Net

One reason people are detained for so long without trial, the government says, is that the justice system is clogged with cases. Prosecutors and courts cannot keep up with the sheer number of people getting arrested, a load that grew as Egypt widened its crusade against dissent.

Taking control after the military deposed Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mr. el-Sisi promised security and prosperity — all many Egyptians wanted after years of revolution, chaos and civil strife.

But he has used the pursuit of stability to justify deepening authoritarianism.

Supporters of General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Tahrir Square in Cairo on the day of the military coup in 2013 that brought him to power.

Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

First, his government rounded up members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist movement that had held the presidency before Mr. el-Sisi took over, accusing it of responsibility for the militant attacks then tormenting the country. Seeing the Brotherhood as a political threat, the authorities also targeted anyone suspected of Brotherhood membership and anyone who had participated in Brotherhood-led demonstrations.

Next into detention cells came a growing number of opposition politicians, activists, journalists and academics. About 110 activists, 733 members of the media and 453 academics were arrested from 2013 to 2020, the justice system monitoring group said.

Eventually, the repression vacuumed up ordinary protesters and citizens.

When a rare smattering of anti-government protests broke out in 2019, at least 4,000 people were arrested, rights groups and lawyers estimate, including many who said they were just passing by.

Those arrests were a prelude to a much broader crackdown in which the authorities, mindful of the Arab Spring uprising that overthrew a previous president in 2011, sought to head off further unrest by arresting people they believed might have subversive ideas.

In downtown Cairo’s Tahrir Square, where Facebook and Twitter helped muster hundreds of thousands of protesters in 2011, security officers began arresting passers-by after stopping them at random and searching their phones and social media accounts for political content. A dedicated unit at the Interior Ministry also combs social media for posts criticizing the government, detaining some users simply for liking and sharing others’ posts, rights groups and lawyers said.

During politically sensitive anniversaries such as that marking the 2011 revolution, the police conduct raids and establish dragnets to pick up young men walking near protest hot spots.

A rare anti-government protest in Cairo in 2019. At least 4,000 people were arrested.

Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

More than 16,000 people were detained, arrested or summoned by the security services for political reasons from 2020 to 2021, according to the Egyptian Transparency Center, a figure that does not include arrests in North Sinai, where the government is fighting an Islamist insurgency and little public information is available.

Most of them went straight into pretrial detention, though most do not appear in The Times’s estimate, since many were released before the five-month mark where our data began.

The surge of cases has jammed the system, backing up the courts and overcrowding prisons.

Terrorism court judges commonly struggle to get through the docket. Lawyers said they had seen sessions in which as many as 800 defendants remained packed into glass cages well past midnight.

The backlog, said Maj. Gen. Khaled Okasha, head of the Egyptian Center for Strategic Studies, a government-aligned research institute, makes long waits before trial “inevitable.”

It has also generated a prison-building spree. Egypt has built 60 new prisons since the 2011 revolution, almost all under Mr. el-Sisi, according to news reports and the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, which was recently forced to disband amid sustained government harassment.

Missing

When people disappear in Egypt — hustled from their homes by armed men in the middle of the night, seized from the street as they walk through downtown Cairo — no phone call is allotted to them. Families might wait months before learning that their loved ones have entered the limbo of pretrial detention. Some never hear a word.

Parents and siblings go knocking at police stations and national security offices, often only for officials to deny holding their relatives. It can take a week or two for suspects to be taken to a prosecutor’s office in Cairo for questioning, lawyers say.

Sometimes their lawyers are waiting for them, alerted by families who presume they have been arrested. Human rights attorneys have developed a simple way to check: At hearings, they hold up a single sheet of white paper with a handwritten name, hoping someone will wave back from the defendants’ cage.

Police officers guarding 739 defendants in a soundproof glass cage in a makeshift courtroom in Tora Prison in 2018.

Amr Nabil/Associated Press

Volunteer defense lawyers who come to court each day jump in to represent other detainees, the only way for some to tell their families where they are.

“The families are thrown into a vicious cycle of uncertainty because they might be dead,” said Mr. Ali, the rights lawyer. “Sometimes they wish for them to turn up at the prosecution, because then they know they’re alive, at least.”

Egypt’s Response

Stung by international criticism of its human rights abuses and anxious to appease a new American president who had vowed “no more blank checks” for Mr. el-Sisi during his campaign, the Egyptian government unveiled a “national human rights strategy” last fall. This year, as economic pressure mounted at home, Mr. el-Sisi launched a “national dialogue” — a chance, he said, for the opposition to return to the political fold and push for reforms.

A presidential committee began pardoning dozens of political detainees. Pro-government figures publicly discussed reining in the length of pretrial detentions, suggesting that such measures could be softened now that the government had largely suppressed terrorism and restored stability.

The amnesties reflected the government’s “eagerness to open up to all political forces and its readiness to create a real will to engage in the national dialogue that the president has called for,” Mr. el-Khouly, who serves on the pardons committee, said in a TV phone-in last month.

But even as it released some dissidents and opposition politicians, it sentenced others to prison, including, in May, a former presidential candidate arrested after criticizing Mr. el-Sisi. Politically motivated arrests continued apace. And detainees’ families say that abuses in the prisons have not stopped.

Most Egyptian officials asked about the pretrial detention system declined to comment for this article. Requests sent to the state prosecutor’s office, prison officials and the presidency through a government spokesman received no response.

Mr. Sallam of the National Council for Human Rights acknowledged that there were some “transgressions” in the justice system, but said that foreign rights groups and spies had exaggerated such problems to undermine the government.

In January, the Biden administration decided to withhold $130 million of the $1.3 billion in military aid the United States gives Egypt every year as a legacy of Egypt’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel, saying that its human rights reforms fell short of what the administration had pushed for.

But the administration released another $170 million that was also supposed to be contingent on reform. And there was a consolation prize: a $2.5 billion arms deal, unveiled just days before the aid cut.

Search for a Son

Sometimes the detained simply disappear into the maw of the system, never to be found again.

Abdo Abdelaziz, 82, a pickled fish trader whose small, concrete-walled apartment in the southern city of Aswan is pungent with his wares, spent the first few days after security officers arrested his son in October 2018 waiting at the police station.

He was certain his son, Gaafar, would be out soon: Gaafar was a driver, he said, a father of four with no time for politics.

“When I’d hear about someone being arrested, I’d think they must’ve done something wrong,” he said. “But because I know we’re not political, we’re not fundamentalists, I figured they’d let him go.”

When they said Gaafar was not there, he went to the courthouse, where defense lawyers said it was unsafe for them to help. Next he contacted Egypt’s chief prosecutor. When no reply came, he went to Cairo for the first time in his life on the 15-hour train, determined to shake something loose.

Turned away, he was passed off to an Aswan prosecutor, who he said asked him why he was making trouble and dismissed him.

“I thought the law was being respected, the Constitution was being respected — that’s why I went,” he said. “And I found none of that.”

Neither office replied to requests for comment.

Gaafar Abdelaziz

Unscrupulous lawyers pounced on the salesman’s desperation, telling him Gaafar had been charged with joining a terrorist group. They said they could find Gaafar — maybe even help Mr. Abdelaziz see him — for about $640.

He paid. Back he went to Cairo, another 15 hours on the train, but he never saw his son.

When nothing else worked, he tried a new approach: He went to every ward in Cairo’s notorious Tora Prison, telling the guards he was there to visit his son on the off chance that they would confirm that Gaafar was there.

The guards checked their records. They said Gaafar was not listed.

Out of ideas, Mr. Abdelaziz returned to Aswan.

More than three years later, he felt something like hope when Mr. Biden was elected.

“With Biden, maybe freedom will have some value,” Mr. Abdelaziz said.

After the American election, Egypt released more than 200 prisoners in what some interpreted as a good-will gesture toward the incoming American president.

Soon after, rights lawyers said, at least 140 of them were recycled into new cases.