ITAQUAÍ RIVER, Brazil — It was 4 a.m., the sun had yet to rise over the Itaquaí River deep in the Amazon, but a team of Indigenous men was already busy preparing a breakfast of coffee, fried meat and fish. They worked on the small stove in their patrol boat, where they had lived for the past month, on the hunt for poachers.

They were up early this Sunday because a few planned to escort their two guests 50 miles back to town.

The guests, Bruno Pereira, an activist training the Indigenous patrols, and Dom Phillips, a British journalist documenting them, had to get back to meet with the federal police. Mr. Pereira was to turn over the patrol’s evidence of illegal fishing and hunting in this remote corner of the vast forest.

It was dangerous work. Mr. Pereira had been threatened for months. A day earlier, Mr. Pereira had seen a poacher armed with a shotgun who weeks earlier had fired a shot over his head. The poacher recognized him. “Good morning,” he shouted at Mr. Pereira.

But at breakfast, Mr. Pereira announced that he and Mr. Phillips would not need escorts. Instead, they would move fast and travel alone. They packed their small metal boat, turned on the outboard motor and headed off. They carried plenty of fuel, the evidence — and a gun.

Then, they vanished.

In the Amazon, such disappearances often go unnoticed. It is a period of growing lawlessness in the world’s largest rainforest, and this isolated patch near the borders with Colombia and Peru has been largely abandoned by the Brazilian government.

But this time was different — there was an international outcry. Mr. Phillips was a freelance writer for the British newspaper The Guardian and Mr. Pereira was once Brazil’s top official on isolated Indigenous groups. The government had to respond.

Within days, the authorities had arrested two poachers who eventually confessed to killing the men and dismembering their bodies. One was the man who had shouted “Good morning.”

The murder of Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips is the story of two men killed while pursuing their passions. Mr. Pereira wanted to protect the Amazon and the Indigenous people who live there. Mr. Phillips wanted to show how Indigenous communities were trying to defend themselves from poachers who often operate with impunity.

But it is also a story with global resonance. The Amazon is crucial to slowing global warming, is overflowing with wildlife and natural resources and is home to isolated communities that preserve a culture and way of life largely forgotten to modernity.

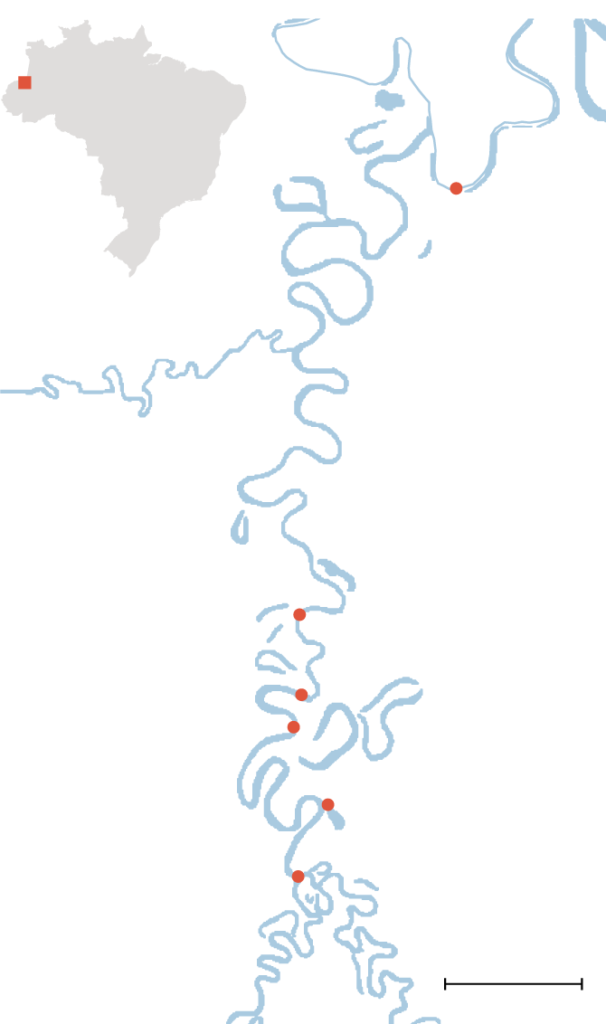

To reconstruct what happened, I retraced the men’s journey down the Itaquaí, collected their correspondence and spoke to more than three dozen people who knew the men, encountered them along the way or investigated their disappearance, including Indigenous activists, fishermen, government officials, police investigators, innkeepers, cooks, family and colleagues.

Police officers last month with Amarildo Oliveira, in the hooded jacket, who confessed to killing Mr. Pereira and Dom Phillips.

Police officers last month with Amarildo Oliveira, in the hooded jacket, who confessed to killing Mr. Pereira and Dom Phillips.

What became clear was that the Brazilian government’s near desertion of this region, combined with President Jair Bolsonaro’s calls to develop the Amazon, has helped embolden the illegal fishermen, hunters and criminal networks that invade the Indigenous territories here.

The few federal officials left in the region complained of being abandoned, while others wore bulletproof vests because of increasing threats.

Mr. Pereira had quit the Bolsonaro administration to protest its environmental policies and began helping Indigenous groups police the forest themselves.

That made him a target. In March, an Indigenous association received an anonymous note threatening him by name. Then the fisherman shot at his boat from a riverside hut. Mr. Pereira decided he needed a bigger gun.

“It’s a pump-action, 12-gauge,” Mr. Pereira said in a message to a former government colleague. “If you’re going to be in the forest, then you need something more brute.”

The shotgun that Bruno Pereira, who was killed in the Amazon, bought for protection.

Bruno Pereira

But Mr. Pereira ultimately declined offers of additional security for his final trip, according to colleagues, while it appeared that Mr. Phillips had not been made fully aware of the threats.

Mr. Pereira, 41, and Mr. Phillips, 57, traveled down a stretch of the Itaquaí sandwiched between the Javari Valley — an Indigenous reservation the size of Portugal that is home to at least 19 isolated groups — and poor, crime-ridden cities at the nexus of Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The plan was to spend several days with the Indigenous patrol before delivering the patrol’s evidence to the police.

Two days before they left, Mr. Pereira sent a colleague a message. The trip, he said, could “give me some trouble.”

The federal agency base that guards the entrance to the Javari Valley reservation in Brazil.

‘Look around. It’s empty, right?’

In 2018, Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips spent 17 days in the same region searching for an isolated tribe. Mr. Phillips described Mr. Pereira as a “burly, bespectacled” man who “cracks open the boiled skull of a monkey with a spoon and eats its brains for breakfast as he discusses policy.”

Mr. Pereira was working for Funai, the federal agency tasked with protecting Brazil’s Indigenous groups, and oversaw the Javari Valley region.

The area has long been racked with conflict between Indigenous groups and poachers who encroach on their reservations. They hunt tapir, peccary and yellow-spotted river turtles, but their biggest prize is pirarucu, a prehistoric, air-breathing fish that grows up to 10 feet long and fetches at least twice the price of many other catches.

Poachers “invade everywhere around here; they’re like ninjas,” said Eumar Vasques, an official at the Funai base that guards the entrance to the Javari Valley reservation, floating in a boat near an empty watchtower. “They know the forest better than we do.”

Illegal fishing has devastated the population of pirarucu — and made it a staple on menus across the area. But fishermen are rarely caught, partly because there are fewer authorities policing them than there used to be.

Fishermen cleaning pirarucu in Maraã, Brazil. The pirarucu, a prehistoric, air-breathing fish that grows up to 10 feet long, fetches at least twice the price of many other catches.

Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

Fishermen cleaning pirarucu in Maraã, Brazil. The pirarucu, a prehistoric, air-breathing fish that grows up to 10 feet long, fetches at least twice the price of many other catches.

Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

The environmental police force, which is charged with combating poaching, closed its regional base in 2018. Its closest office is now 700 miles away — the distance between New York and Chicago. The federal police are more than an hour away. The Brazilian Navy and Army do not regularly patrol the waters. And in Atalaia do Norte, the closest town, the state police lack a boat or even radios.

“Look around. It’s empty, right?” Mr. Vasques said. “And there’s more trafficking in this region than anywhere.”

Funai is the only regular government presence on the Itaquaí, and the staff at the base, including temporary Indigenous workers, is down to eight people from nearly 30 in years past, Mr. Vasques said. As a result, illegal fishing is no longer a focus. “The base’s fundamental role is not really inspection,” he said. “Our role really is to protect these isolated tribes.”

Funai said in a statement that it had increased its budgets in recent years. Agency employees in the region said much of that money had gone to feeding Indigenous groups. Since Mr. Bolsonaro took office in January 2019, Funai’s full-time staff has fallen by 15 percent to about 1,500 employees, federal statistics show.

Mr. Bolsonaro has said that the government continues to prosecute people who illegally deforest and poach in the Amazon. He has also argued that Brazil’s environmental regulations limit the full economic potential of the rainforest.

In place of the state, Indigenous men here have become the forest guardians. Since last year, 13-man patrols track illegal activity inside the region’s reservations. Mr. Pereira trained the men to document crimes using smartphones and drones.

In late March, a patrol led the authorities to a poacher who was arrested with 650 pounds of illegal game and nearly 900 pounds of pirarucu.

The Itaquaí River, near the Funai base and Javari Valley reservation that is home to a number of isolated Indigenous groups.

The Itaquaí River, near the Funai base and Javari Valley reservation that is home to a number of isolated Indigenous groups.

‘It’s going to get worse for you’

Around the same time, a handwritten note arrived at Univaja, an Indigenous association helping organize the patrols. “Bruno of Funai is who’s sending the Indians to seize our boat engines and take our fish,” it said, referring to Mr. Pereira. “If you continue this way, it’s going to get worse for you.”

The note was alarming. A colleague of Mr. Pereira’s at Funai had faced similar threats in 2019. He was then shot twice in the head on his motorcycle.

That killing, which is unsolved, prompted Funai to add armed guards to its outpost on the Itaquaí. When I arrived by boat, Mr. Vasques came out in a bulletproof vest and accompanied by two bodyguards. “In the beginning, we didn’t have these sorts of threats,” he said. “They’ve just gotten more and more angry.”

From 2010 through 2020, 377 people trying to defend land from invaders were killed in Brazil, according to Global Witness, an advocacy group. Over roughly the same period, just 14 of the more than 300 killings in the Amazon went to trial.

Weeks after the threatening message, Mr. Pereira and a Univaja colleague were on the Itaquaí when a shot rang out, the projectile flying over their heads. Then they saw Amarildo Oliveira, a fisherman known locally as Pelado, standing on his porch with a gun.

Mr. Pereira had carried a .380-caliber pistol with 18 rounds. He decided to upgrade.

“New toy being tested today,” he wrote to a friend in May, attaching a photo of a shotgun in front of a target riddled with bullet holes.

The police and military during a search for Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips last month in Atalaia do Norte, Brazil.

The police and military during a search for Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips last month in Atalaia do Norte, Brazil.

‘He had complete confidence in Bruno’

After two decades writing about electronic dance music, Mr. Phillips arrived in Brazil in 2007 and began a second act as a foreign correspondent, writing for several publications, including The Times.

His latest project was a book about the creative ways people were trying to save the Amazon. He faced a tough deadline and a dwindling budget when he decided to take a final reporting trip, a reunion with Mr. Pereira in the Javari Valley.

Mr. Phillips was usually fastidious about security, writing detailed memos for his wife and editors. But this time he didn’t, family and colleagues said.

Alessandra Sampaio, his wife, said Mr. Phillips spent days studying maps and talking to Mr. Pereira. “He had complete confidence in Bruno,” she said.

On Tuesday, May 31, he began a two-day journey to Atalaia do Norte, a town of 20,000 people at the start of the Itaquaí.

One of the few main roads in Atalaia do Norte, a town of 20,000 people at the start of the Itaquaí River.

One of the few main roads in Atalaia do Norte, a town of 20,000 people at the start of the Itaquaí River.

When he arrived on Wednesday, he interviewed Orlando Possuelo, Mr. Pereira’s colleague in training the Indigenous patrols. Mr. Possuelo told Mr. Phillips about the fisherman who had shot at Mr. Pereira.

“He didn’t know,” Mr. Possuelo said. “He was surprised.”

Ms. Sampaio said her husband never mentioned the shooting. “He spoke in general terms that Bruno had been threatened,” she said. “But Bruno had been threatened for many years.”

Two Univaja officials asked Mr. Pereira if he wanted to take two bodyguards on the trip, but Mr. Pereira declined.

That Thursday, when Mr. Phillips was leaving his small hotel, he gave the staff a false itinerary. He said they would head west, though they were actually journeying south. Colleagues said Mr. Pereira often did this to avoid being followed.

As Mr. Possuelo helped carry gear to the boat, Mr. Pereira told him that Mr. Phillips was worried. Mr. Phillips had asked about the fisherman shooting at Mr. Pereira, but Mr. Pereira assured him everything would be fine.

“Bruno was almost joking about it,” Mr. Possuelo said. “We live with these threats,” he added. “So sometimes, we deal with them with a certain lightness.”

Mr. Phillips sent his wife the Univaja president’s contact information. “I think I’m only going to have cell signal again on Sunday,” he said.

“I love you,” she replied. “Be careful.”

The two men pushed off from the port. Mr. Phillips had notebooks, cameras and his iPhone. Mr. Pereira was carrying his gun.

A colleague snapped the last known image of the pair, sitting side by side as they headed down the Itaquaí.

The last known photo of Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips.

‘They might want to do something to him, kill him’

After three hours, they arrived at the last house before the Javari Valley reservation, an open-air hut with a tin roof, no electricity and a broken refrigerator leaning against the porch. They were staying with a local fisherman and his dog, Black.

Also waiting for them was the Indigenous patrol.

On Friday, Mr. Phillips interviewed the Indigenous men and watched them patrol. At night, some Indigenous men cooked sloth. Mr. Pereira tried it; Mr. Phillips declined.

Early the following morning, Mr. Oliveira, the fisherman who had fired at Mr. Pereira, passed in his boat with two other men, heading toward the reservation. Some of the Indigenous men pursued them. As they approached, Mr. Oliveira and another man held shotguns over their heads.

Mr. Oliveira cut his engine and allowed the current to carry him slowly past where Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips were staying.

Mr. Pereira was drinking coffee. He saw that Mr. Oliveira wore an ammunition belt and asked Mr. Phillips to take photos.

“Good morning,” Mr. Oliveira said loudly to Mr. Pereira. “Good morning,” Mr. Pereira replied.

Later that Saturday, the group agreed that two men from the Indigenous patrol would accompany Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips on their ride back the next day.

But during breakfast, Mr. Pereira said they would return alone. No one would expect them to leave so early, he said.

They departed about 6 a.m., carrying the patrol’s photos and location data about poaching.

On their way back, Mr. Pereira had an errand to run. He stopped at a riverside community, São Rafael, to try to schedule a meeting about a sustainable-fishing program to replenish the stocks of the giant pirarucu.

The community leader they were looking for was not there, so they spoke to Jânio Souza, another fisherman. Mr. Souza said that Mr. Pereira mentioned the threats and showed him his gun. “He said that they might want to do something to him, kill him,” Mr. Souza said.

Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips left. They were last seen passing the next community on the river, São Gabriel, where Mr. Oliveira lived.

Police officers carrying the bodies of Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips in Atalaia do Norte.

Police officers carrying the bodies of Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips in Atalaia do Norte.

‘Or is it something bigger?’

Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips were speeding down the Itaquaí when they were caught by a much faster boat.

That boat carried Mr. Oliveira and another man, Jefferson da Silva Lima, who fired at them with shotguns. Mr. Pereira was shot and returned fire, the police said, but missed. Eventually the boat crashed into the brush.

An autopsy concluded that Mr. Pereira had been shot twice in the chest and once in the face. Mr. Phillips was shot once in the chest.

The police arrested Mr. Oliveira, Mr. da Silva and Mr. Oliveira’s brother, who they said helped dismember and hide the bodies in the forest. Their lawyers declined to comment.

The authorities said they were investigating whether the killings were connected to organized crime groups that finance and direct much of the poaching the patrols are fighting.

“Was this just a fight between Bruno and Pelado?” said Eduardo Fontes, chief of the federal investigation into the murders, using Mr. Oliveira’s nickname. “Or is it something bigger?’’

The motor on Mr. Oliveira’s boat can cost about $10,000, or roughly what a fisherman here makes in a year. The authorities said his poaching was probably sponsored by more powerful criminals.

Investigators believe Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips’s boat crashed here in brush along the Itaquaí River.

Investigators believe Mr. Pereira and Mr. Phillips’s boat crashed here in brush along the Itaquaí River.

The police arrested Rubens Vilar Coelho, a Peruvian man, last Friday for presenting a false identification while being questioned about the murders. Mr. Coelho is one of the area’s largest buyers of fish and told the police he bought fish from Mr. Oliveira. He denied any connection to the killings, the police said.

After his trip, Mr. Pereira had been scheduled to visit a different Indigenous group to learn tips about patrolling the forest.

Mr. Possuelo took Mr. Pereira’s place. He also planned a shopping trip. “I’m buying the same gun as Bruno,” he said.